‘Now war arose in heaven, Michael and his angels fighting against the dragon; and the dragon [the devil] and his angels fought, but they were defeated and there was no longer any place for them in heaven.’ Revelation 12:7

Like generations before me, I have become enamoured with a rocky outcrop outside Marazion in Cornwall, better known as St Michael’s Mount.

Rising enigmatically out of the sea’s vapours like a dream or fairytale, St Michael’s Mount is a tidal island in Mount’s Bay, only accessible via a narrow cobbled causeway when the tide is out. The islanders are essentially marooned for sixteen out of twenty four hours, lending it an ethereal, elusive quality, with visitors eagerly anticipating the small gap through which to embark on their own pilgrimage to the castle.

The Mount has undergone several transformations. Once a spiritual house of worship and place of pilgrimage, it transitioned into a fortified stronghold before settling into a family home. Throughout the ages, many have been drawn to its natural advantages and access to the high seas, but it has remained impenetrable, its sheer rock face seemingly unassailable, rising above the land around the shore; its church surrounded by a walled castle at the top of the rocky outcrop with a single track leading down to a few fishermen’s huts and an enclosed harbour.

The castle’s rooftop gives commanding views over the open sea and Marazion:

As Marazion local and author of ‘about St Michael’s Mount,’ Michael Sagar-Fenton says, it always looked ‘just right,’ at ease in its natural surroundings.

No written record exists of the Mount’s formative days, it was most likely a rocky promontory before leaving the safe harbour of land to favour the open sea. Its name supposedly derives from its magnificent namesake in Normandy, UNESCO World Heritage site, Mont St Michel.

Where the former is a medieval city and monastery, the latter is a bastion of natural defence, attractive to those looking for a stronghold or a shipwreck’s bounty, the latter being a frequent problem as many a ship or boat would fall victim to an unforgiving south westerly wind around the island.

The Mount’s spiritual heritage hearkens back to the early Celts, when a group of Celtic missionaries, known as The Saints, marked numerous places in Cornwall as places of worship and bestowed upon them sanctified names. Following the saints came the pilgrims and consequently the foundation for the Mount’s future role in the coming years. Penance and absolution were necessary to enter heaven, so extravagant journeys of pilgrimage were made by those who had the resources, supporting the small local community through tithes of fish.

After the Norman invasion, William the Conqueror bestowed the county to his half brother, Robert. The latter then gave the local village permission to hold a Thursday market to financially aid Mont St Michel, naming themselves ‘Marghas Yow,’ and a nearby settlement became known as ‘Little Market’ or ‘Marghas Byghan; from these come the derivatives, Market Jew and Marazion.

The ‘Pilgrim’s Steps:’

In 495 came a miraculous apparition, with several fisherman claiming a vision of St Michael standing upon a rocky outcrop on the western side of the island. Thus the island transformed from simply a trading port to a significant location in Christendom.

Sculpture depicting the Mount’s namesake, Michael the Archangel, and his defeat over the devil:

In 1135 the Abbot of Mont St Michel established a Benedictine priory on St Michael’s Mount as a subsidiary of his own. However tributaries were suspended during wartime, which gradually eroded their bond. Links were finally severed during the reign of Henry V, at which point the Mount became an independent institution. It was now property with income attached, no longer a sanctified refuge. Although there are few footnotes in history pertaining to its conquest by enemy forces, its strategic advantages undoubtedly made it attractive to both the monarchy and outsiders. After years of wresting it from the monarchy, Syon Abbey eventually regained control of the Mount.

During this period of unrest, the Mount was undoubtedly transitioning from a spiritual place of worship to a fortified stronghold.

A line of cannons overlook the harbour and open sea, reminders of its military heritage:

Due to its strategic advantages, the island survived Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries and the 14th century church remains to this day, the ‘centrepiece of the castle.’ Despite its survival, the faithful clergy were sadly sent away, instead replaced by the Milliton family of Pengersick, who rented it from the monarchy on the condition that they repaired the buildings and pier and supported a garrison of five soldiers.

Stained glass at the castle:

As the tin trade flourished, so did the communities at neighbouring Mousehole, Newlynn, Penzance, Marazion and the village on the Mount. The island was no longer the only significant port, but its fortifications made it the most vital. In July 1588, the beacon on the mount was lit as the Spanish Armada advanced up the English channel to its forthcoming defeat by Howard and Drake.

Oil painting depicting the first beacon to warn of the Spanish Armada, 1588:

The Spanish invaded Brittany instead, but an embittered raiding party razed Paul, Mousehole, Newlynn and Penzance in revenge. The Mount was too much of a challenge and Marazion was the largest community in the area left standing.

In 1599 many church lands were sold by Elizabeth I into private hands and Robert Cecil, later Earl of Salisbury, bought the Mount. It was a formidable challenge to invading forces, with a new threat rising from the Dutch and North African pirates from Salee and Algiers, who were known to take hostages as slaves.

In 1640 the Mount was sold to Sir Francis Bassett, however two years after their acquisition, they became embroiled in the civil war, with Bassett one of the king’s most faithful soldiers. However, they were forced to pay extortionate fines after Cromwell’s victory (Cornwall was emphatically Royalist) and despite their tin revenues, they parted with the Mount in 1659.

Oil painting depicting the surrender of the Mount after the civil war, 1646:

Unfortunately for the Bassetts, the purchaser, John St Aubyn of Clowance, was a prominent Parliamentarian and was appointed Captain of the Mount by parliament after the war. The family remained custodians for the next three hundred years and still are today. The last garrison departed in 1660 by which time the Mount was in a poor state. However with the end of international and local hostilities and the beginning of the golden age of tin and copper, time and money was at their expense. One of the early improvements was the reowned frieze in the ‘Chevy Chase’ room, the monk’s old refectory and much of the Mount as we know it now originated from this period of renovation, making it more befitting to a country house.

The resplendent banqueting hall in the older part of the castle:

The St Aubyns mostly followed careers in the army and parliament, many distinguishing themselves through military exploits.

Fencing equipment mounted in the entrance hall:

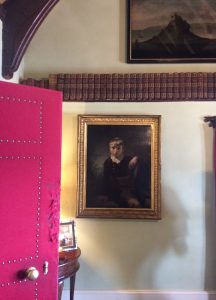

An exception was the fifth baron, known as a patron of the arts, particularly for sponsoring the Cornish artist John Opie. The family’s affection for the arts continued for generations and they still continue to support and encourage living artists.

Examples of their extensive art collection:

The Napoleonic wars led to renewed tension and further fortifications, using the impressive line of cannons to disarm the enemy. At its peak, the island supported 300 people, a school and three pubs. Marazion was declining as a fishing port at this time and both Marazion and the Mount were not previously places the gentry would want to inhabit. However with the ascendancy of the railway, the Mount became a genteel resort for affluent visitors. The island’s business was mainly fishing for pilchards, although many men also doubled as boatmen and estate workers.

The causeway was not properly laid until 1898, before which it was a natural shingle bank, laid by natural confluence of the tides. In the 1950s, the family decided to gift the castle to the National Trust as a means to conserve it for the future. The castle and older parts of the house were opened to the public and the 19th century house, with kitchens and ‘one of the most romantically set dining rooms in the world’ remains private.

Rooftop view of the sub-tropical garden:

Its appeal endures, with artists from Turner to the cartoonist Giles attempting to capture it through its evanescent changes, in sunlight, dusk or moonlight. The Mount is known, justifiably, as the jewel in Cornwall’s crown, an emblem for the whole county. Even mystical straight ley-lines are present, which are said to link places of supernatural power and often high places dedicated to St Michael.

Pre-Christian beliefs also favoured the island as a place of magic and many today find their dreams of fairy stories fulfilled. The Mount also has its own mythology, concerning Jack the Giant Killer, where the giant Cormoran lived in the island.

The Giant’s well, halfway up the Pilgrim’s steps:

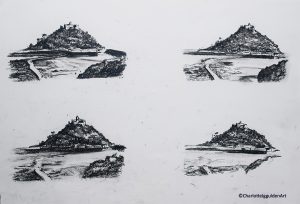

This is my charcoal interpretation of the beguiling changing tide at St Michael’s Mount, with Chapel Rock in the foreground: