‘I saw the angel in the marble and carved until I set him free.’ Michelangelo

Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael. Three names that, after 500 years, need little introduction to a modern audience. These paragons of the Italian Renaissance are generally credited as figureheads of High Renaissance art, imbuing their works with a psychological astuteness and dynamism, which visually embodied the prevalent resurgent interest in classical ideals after a period of cultural stagnation.

The National Gallery’s recent exhibition, ‘Leonardo, Michelangelo, Raphael about 1500’ aimed to explore an artistic dialogue that was initially friendly and respectful, but became at times contentious, due to the competitive nature of commissions available in Rome. The exhibition gathered together eight works by the three artists, showcasing how they learnt from, and sometimes ‘borrowed,’ from one another.

Acutely aware of one another’s presence in the social arena, each artist sought to be distinctive in his vision and execution:

Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), often described as the ultimate Renaissance Man, achieved mastery in many fields of study, combining both science and art in his craftsmanship. His initial desire was to work as an inventor of military weapons for the Duke of Milan, but was instead commissioned as the official painter for the court and subsequent wealthy patrons. He amassed hundreds of drawings of his ideas, leaving him with little time to paint. As a consequence, we have been left with a few examples of his paintings, most notably ‘The Virgin of the Rocks,’ depicting the Immaculate Conception, and Mona Lisa.

‘The Virgin of the Rocks’ (about 1491) by Leonardo da Vinci:

Michelangelo Buonarrotti (1475–1564) was by his own admission, a sculptor first; he expressed the human figure in marble, reimagining its form in all its powerful and physical dynamism. All his projects were vast and ambitious, placing the human body as central to emotional expression.

Raffaello Santi, or Raphael (1483–1520) embodied the classical ideals of harmony and beauty in both his paintings and even temperament. He drew his own study of Michelangelo’s Taddei Tondo and was initially influenced by Leonardo, yet imbued the face of the Madonna with his own preference for serenity and clarity and was a far more prodigious painter than Leonardo.

The Ansidei Madonna (1505), by Raphael:

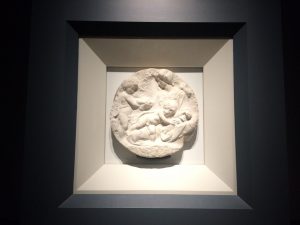

The focus of the exhibition was Michelangelo’s ‘The Virgin and Child with the Infant Saint John,’ also known as the ‘Taddei Tondo’ (1504-5), on loan from the Royal Academy and the only marble sculpture by Michelangelo in the UK.

The psychological immediacy of the sculpture opposed the otherworldly virtues of Leonardo’s painting ‘The Virgin of the Rocks.’ Whereas revelation and relational humanity seems to be Michelangelo’s concern, Leonardo’s appears to be divine worship and reverence, aspiring to the ideals of beauty, similar to the harmonious aspirations of Raphael.

As Matthias Wivel, the National Gallery’s Curator of 16th-century Italian Paintings says: “The ‘Taddei Tondo’ provides a key to understanding Michelangelo’s evolution as an artist, following but also rejecting Leonardo’s example, as well as for the young Raphael’s development of a more expressive, dynamic style in synthesis with what he was simultaneously learning from Leonardo.”

The paintings and drawings on display in total, were: ‘The Virgin and Child with Saint John and Angels (‘The Manchester Madonna’) and The Entombment. Leonardo was represented by The Virgin with the Infant Saint John the Baptist adoring the Christ Child accompanied by an Angel (‘The Virgin of the Rocks’) and The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and the Infant Saint John the Baptist (‘The Burlington House Cartoon’). There were three works by Raphael on display – The Madonna and Child with Saint John the Baptist and Saint Nicholas of Bari (‘The Ansidei Madonna’), Saint Catherine of Alexandria, and The Madonna of the Pinks (‘La Madonna dei Garofani’).’

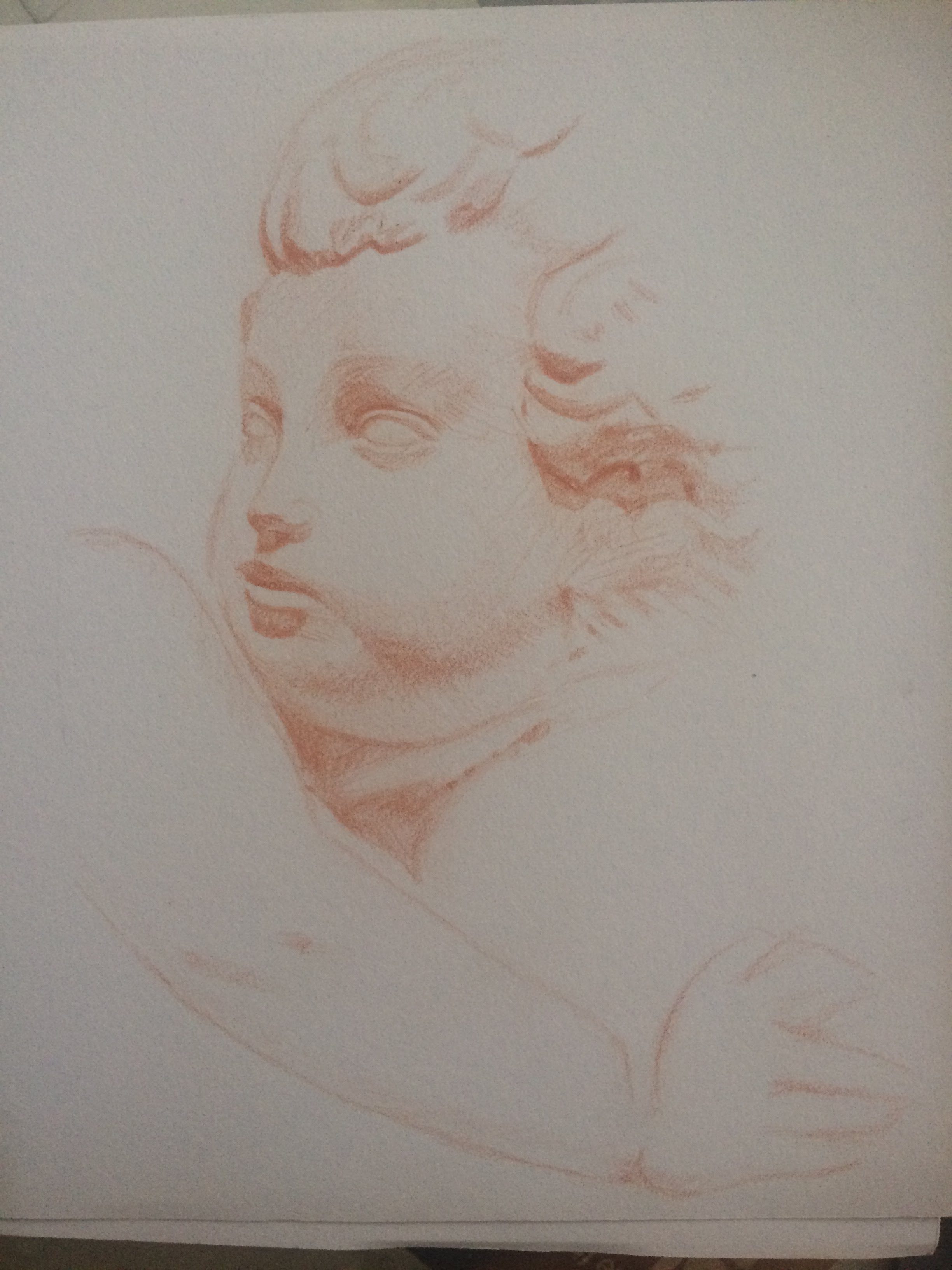

This is my sepia pencil study of Michelangelo’s marble depiction of the Christ Child, Jesus; his face, almost cherub-like, emanates innocence and purity.

Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael were men of their time, yet their vision transcended their history and influenced generations of painters, sculptors and art collectors to come.